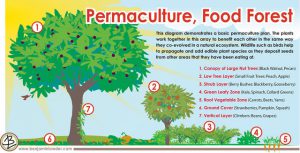

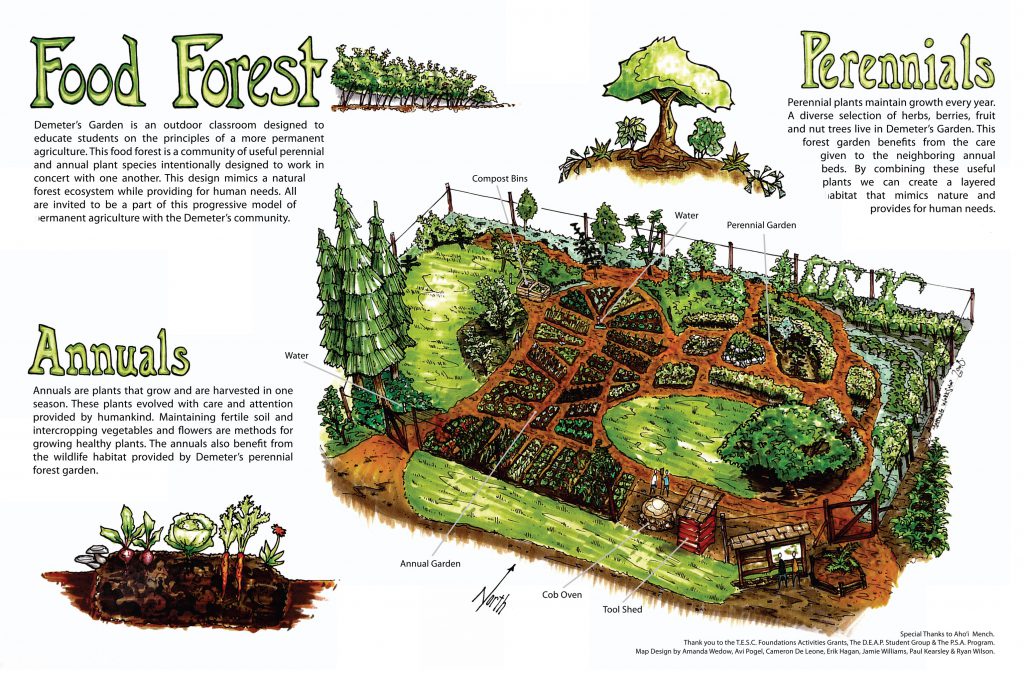

One of the most common inquiries that I received while working at a food forest nursery and educational center in Central Florida was how to build a banana circle. Banana circles have benefits on multiple levels, both for the environment and for the human community.

First, they utilize companion planting so that the growth habits of the various species included benefit that of the others. In essence, they work together symbiotically by providing nitrogen, biomass, shade for other species in the circle, etc. Secondly, banana circles are beneficial because they provide stationary composting scenarios that do not require turning. Lastly, a banana circle provides a way to readily utilize grey water runoff from a house or a well. This is extremely beneficial in both rainforest and (sub)tropical climates because it lessens “open water”. This not only decreases the potential for disease and bacteria, but also eliminates the breeding ground for malaria-causing mosquitoes.

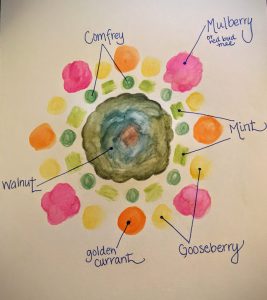

If you are in a tropical or subtropical climate, learning how to grow a banana circle is not only an excellent regenerative agricultural practice, but also a way to bring natural beauty to areas that are often more difficult to design around. So, here are is an easy-to-follow diagram with simple steps for building a banana circle.

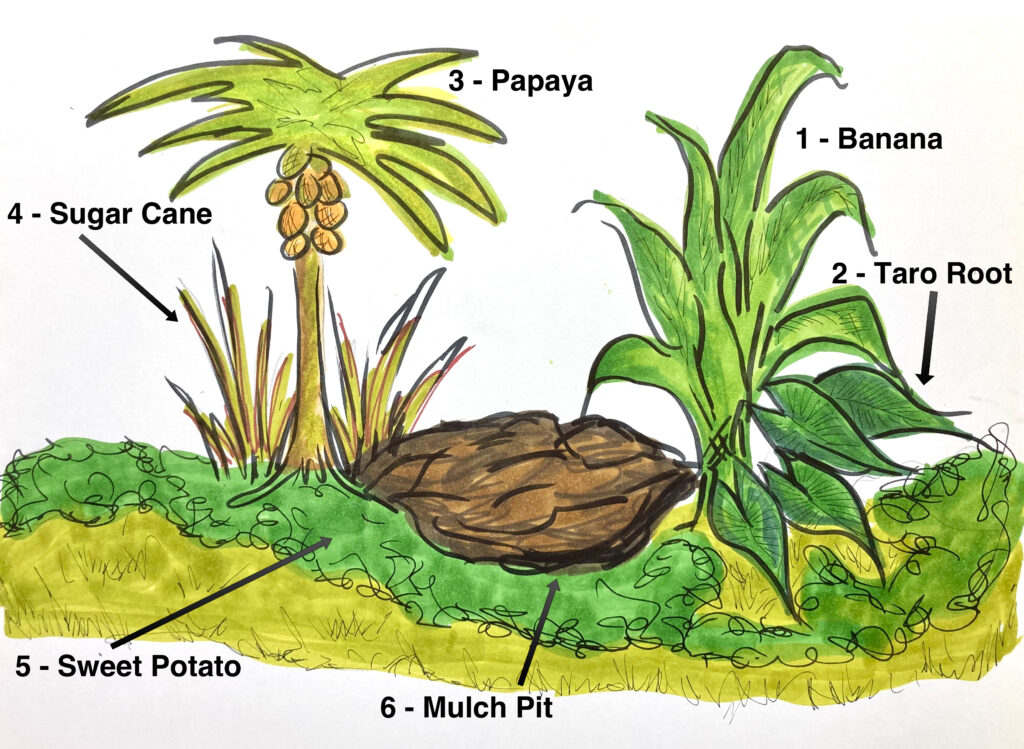

Diagram of How to Building Build a Banana Circle

Simple Steps to Building a Banana Circle

- Dig your hole. A small banana circle should be a bowl-shaped hole that is 1-2 yards in diameter and about 3 feet deep in the center. A larger circle can be 2-2.5 yards in diameter and 3-3.5 feet deep in the center. It is better to have multiple circles this size than to try and make a pit larger than the sizes listed. Otherwise, the organic matter may not decompose quickly enough and it will be harder to harvest crops around the circle.

- Pile the dirt around the outside edge of the hole in the shape of a donut. This circular swale is where you will plant most of your trees. Under the “donut” of soil, you can also bury logs to make huglekultur swales for increased fertility and water retention.

- Fill the pit with mulch and compost. Use kitchen scraps, small sticks, yard clippings, leaves, cardboard, newspaper, etc. Material can continue to be added to this pile as often as needed. Install drainage from existing grey water systems to empty into the pit. Otherwise, if you install pipes or trenches later, you will risk disturbing the plants once they are established.

- Plant around the outside of the circle using the diagram above. If you are doing a larger circle, plant no more than 4 banana plants (at 12, 3, 6, and 9 o’clock) around the circle. This will allow them adequate space to spread out. Beans (not pictured above) can be planted anywhere in the system to fill in space and provide nitrogen for the other plants. Climbing beans can be used on the bananas once they have reached a mature height. In the earlier phases it is best to use bush beans. If you are in the US, I have purchased organic plants for banana circles from A Natural Farm and Educational Center.

- Don’t over plant. Plant quantities for a large (2-3 yard diameter) circle: 4 Banana, 2 papaya, 2 sugar cane, 2 taro, 10-12 sweet potato slips).

- Water. Water the center and harvest the edges.

Banana Circle Maintenance

- Spring (after danger of frost): Cut off dead banana leaves and chop and drop any spent plants and throw them into the center of the circle.

- Add moisture to the center of the pit during the dry season. Water ONLY in the center of the pit. Do NOT water the mound or edges of the swale.

- Keep adding organic matter to the compost pile in the center.

- Plant sweet potatoes farther away from larger plants, for ease of harvest. Add in bush beans in any gaps that you find.

- Mulch on the outside using wood chips to create a path and accessible area for harvesting.

- Consider a late spring foliar spray for papayas to prevent “black spot”.

- Harvest sweet potatoes in the autumn OR once leaves have died back. Be careful to not disturb the tree roots nearby.

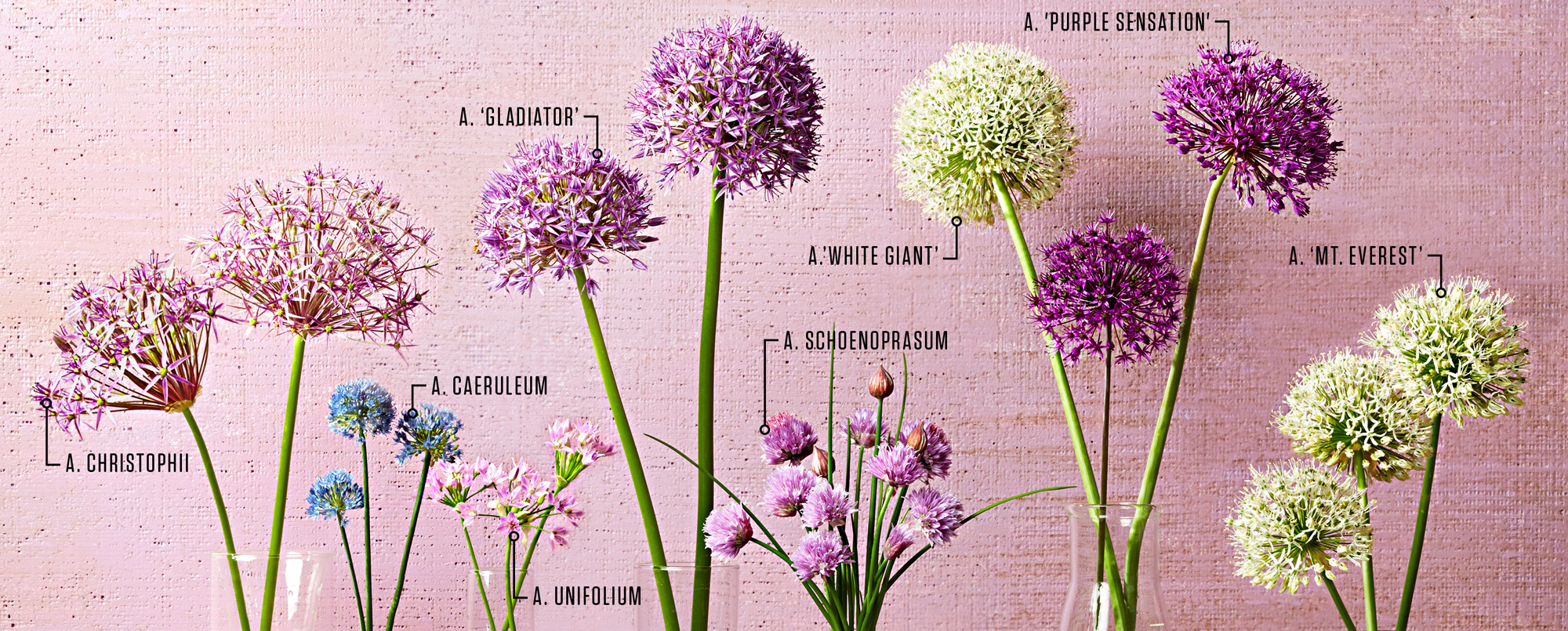

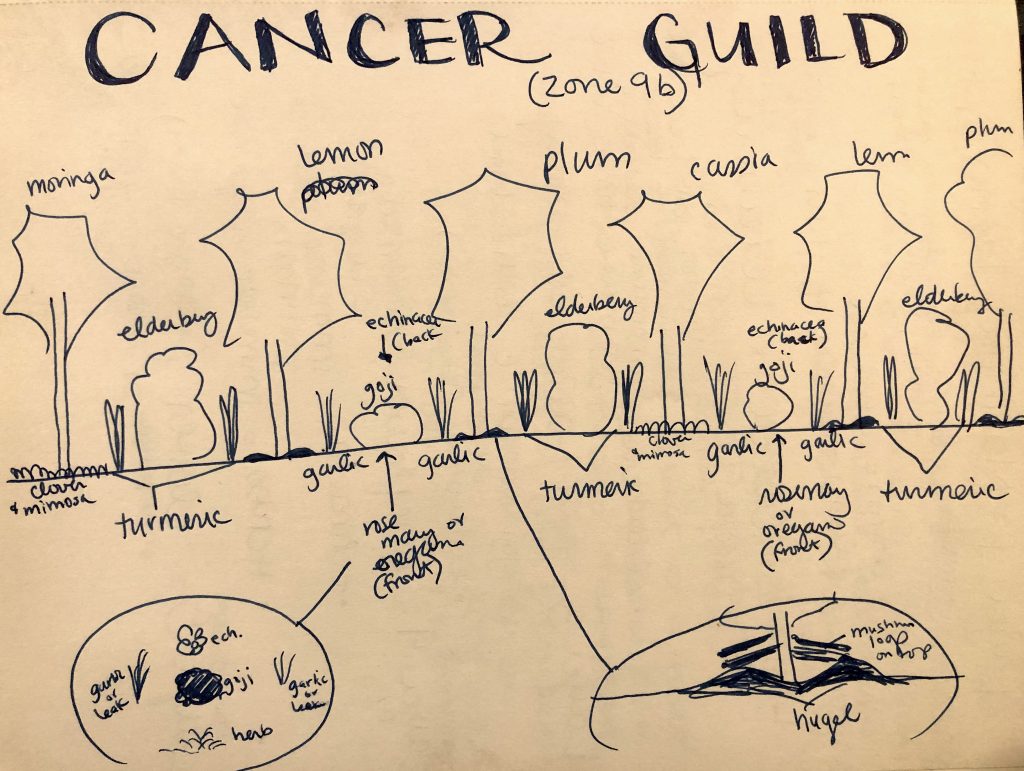

- Consider additional plants: Blackberry, raspberry, ginger, turmeric, and katuk can also be planted nearby or in the shaded areas.

- Consider a linear pattern: The same plants in the diagram and the additional ones listed above can be used in a line as well as in a circle. The key is to make sure they all have access to the mulch pit (in this case trench line)

- Consider pond or wetland areas: These plants can also be planted along pond or water edges in other contexts. Papaya, however, will do better is a well drained (higher up) place in the system).

Banana Circles as a Gray Water Run-off Catchment System

In many tribal communities, the water well is a place of social interaction as much as it meets a practical need. Adding a banana circle to this area helps create a sense of beauty, but is also extremely practical. In many tribal systems, the people will either burn or throw out plant material instead of using it in a composting system. However, changing this simple component can help build their soil, provide food, and bring new strategies of sanitization and disease prevention.

On an ecological level, as the soil improves around these composting circles, the people can then begin to introduce chickens, which will further improve soil quality. The compost will feed the chickens and they will add their own biomass to the system via their droppings. Though it may take a few years to dramatically improve soil quality, the lasting impact of these systems is profound. Utilizing waste water and compostable material is ideal in creating micro-ecosystems that can help restore abundant soil health.

Just to reiterate, standing water (especially in humid climates) can foster disease and bacteria when left untreated. By funneling the run-off water and planting a banana circle, we are not only utilizing the excess water, but also purifying it before it attracts disease and mosquitoes.

The compost pit in the center creates a place for mycelial mass to thrive, which helps destroy many disease causing bacteria. Furthermore, the fungal networks will also act as a way to break down organic matter and fertilize the soil. Palm fronds (specifically) are especially beneficial in this type of a composting system. Essentially, they release phosphate which boosts the networks of mycelium in the soil.

Keep in mind, however, that bananas and mycelium alone can only handle minor pollutants (like grey water, kitchen water, run-off, etc.). Do NOT use this system as a way to use black water.

What additional insight can you provide for others regarding banana circles?

What specific varieties have worked well for you?

Leave your tips in the comments below and tag @permaculturefx on social media so we can share your banana circle posts to further educate others.

Sign-up for our mailing list OR get a permaculture consultation for your property.

Once you have created a few different drawings of your layout, I would recommend sitting on it for a few days and then coming back to it later. Run the ideas by a friend and get their feedback. When I was initially planning my layout, I incorporated too many alkaline loving plants next to my blue berries, which do best with slightly acidic soils. I was so focused on the fruit and berries that I liked, and the way they would look together, that I missed a pretty big piece of the puzzle. The result would have been an environment where likely neither would have thrived, so I was relieved to have the insight from another permaculture eye.

Once you have created a few different drawings of your layout, I would recommend sitting on it for a few days and then coming back to it later. Run the ideas by a friend and get their feedback. When I was initially planning my layout, I incorporated too many alkaline loving plants next to my blue berries, which do best with slightly acidic soils. I was so focused on the fruit and berries that I liked, and the way they would look together, that I missed a pretty big piece of the puzzle. The result would have been an environment where likely neither would have thrived, so I was relieved to have the insight from another permaculture eye.