Why a Food Forest?

In a culture that encourages us to have more money, bigger toys, larger savings, new cloths, and an endless supply of technological gadgets, we should be stepping back and asking, “why?” Do we really need one more gadget? Do we need another nick-knack? Do we need the latest cell phone or computer? Do we actually need the new shirt or pair of shoes or could we just simply wear the ones we already have? We have been trained by a consumer-based culture that more is better.

The reality is that most of these items we are collecting have a short shelf-life. Even our savings accounts, retirement funds, and inheritances we will fade in a relatively short time. Maybe they will last a few years, a few decades, or if we are are extremely wealthy they might last a generation or two. In the context of a century… our stuff will be gone in a heartbeat. But, what if we could pass on a legacy that would last 50-100 years or more? What if our legacy could provide food, shelter, and play areas for your children or grandchildren? What if our legacy provide pollination for wildlife, shelter for birds and animals, and purified the air? What if we could leave a legacy that actually provided a source of LIFE?

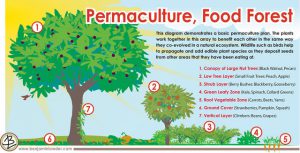

In my humble opinion, one of the most practical ways to accomplish a legacy of this caliber is to plant a midwest food forest. In permaculture, we use this phrase to describe a forest of edible and restorative plants working in harmony with one another.

What is a Food Forest?

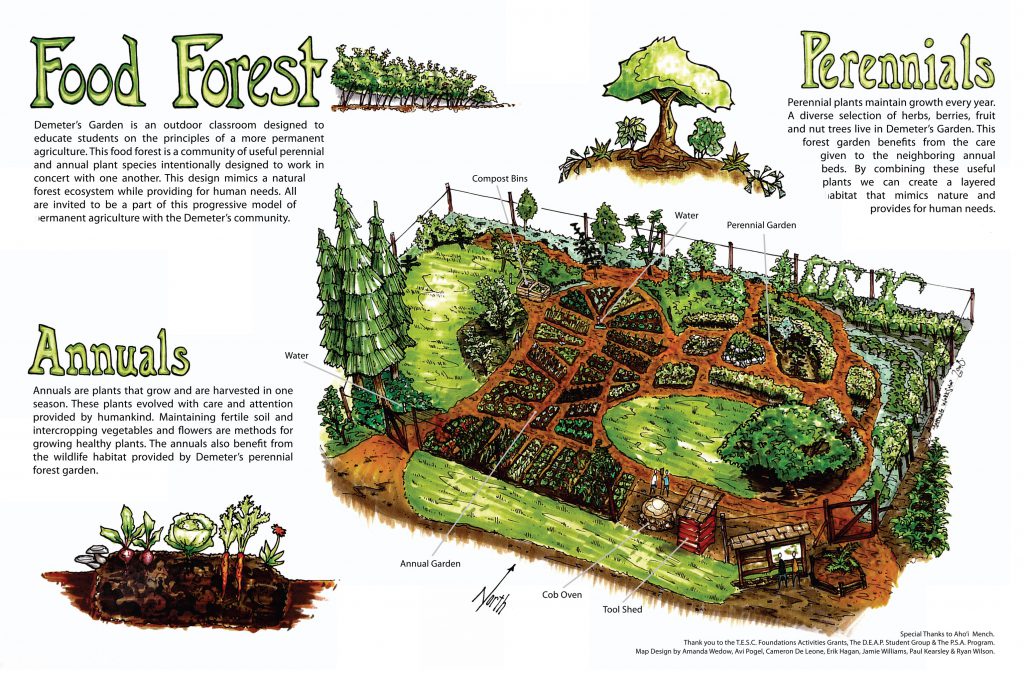

Generally speaking, every forest is jam packed with edible fruit trees, nuts, berries, and fungi. Over hundreds of years, natural succession helps establish these systems and create a healthy and balanced growing environment. Using permaculture, we are essentially designing a system that works in tandem with nature to speed up the process. Instead of productive abundance taking 100 years to be established, we can design it to take only a handful of years. A food forest uses intelligent design to restore and remediate land that would otherwise take centuries to return to a normal state. Instead of working against nature to maintain a mono crop, perfectly green lawn, or a patterned landscape of tropical annuals, we use perennial species that will last foe year. This is especially useful in areas that have suburban forests, because in most cities our forested areas are only 50-70 years old (at best). Historically speaking, many wooded areas were harvested between 1940-1975 for lumber and then either naturally regrew or were replanted. Even the city land behind my house in Kansas City, MO is a fairly young forest and only has a handful of old growth oak trees that are older than 100 years.

A note on removal of invasive species:

Most of the forests in the Midwestern city areas are in similar shape and are nearly all facing the invasive honeysuckle bush invasion. Amur honeysuckle, or Lonicera maackii, was introduced to gardens in New York in the late 1800’s and by 1924 was already labeled as “weedy species”. Since then, it has spread throughout the east coast and midwest and it’s shrub-like structure shades out low growing species in younger forests. It’s red berries are generally ingested by bird species and the seed spread in their stool to other areas. Removing this species is often the first step for Midwesterners starting a food forest.

Once the invasive species has been removed, the land is ready for replanting and reforestation.

How to Plant the Food Forest – Part 1

1 – Land Preparation: In our recent project, we had a great deal of invasive honeysuckle to remove, which was obviously very time consuming. Digging it up is the most effective way, but you can also use a chain saw and cut it off at the ground. When you cut it, you will have to use chemicals to kill the root or it will simply grow back. Obviously, I prefer NOT using herbicides, but there are some natural alternatives that contain orange oil, agricultural grade vinegar (15-30%), and epsom salts.

It’s imperative to properly rid the area of the invasive species, because skipping this step will allow the old species to return and choke out all of your design work. When removing undergrowth species, I prefer to do it in early spring so it’s warm enough to work and you don’t have to worry about ticks or fighting through the leaf growth. If you are fortunate enough to have goats, they will take care of the leaves and branches, but you’ll still need to dig out the root or it will grow back quickly.

The second step in preparing the land is to examine your soil and structure. This is your time to consider amendments. You can bring in compost from a local company, collect fallen leaves from your fall clean-up, add bone or blood meal, or sulphur for acid loving areas. Before adding anything to the soil itself, make sure you are testing and observing your site. Get to know the land you are working with and begin with the end in mind. Know the type of soil your plants will prefer, so you can create the right environment for them.

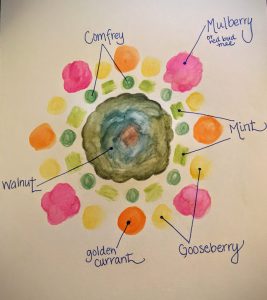

2 – Plan out your design: For every project, I generally need about 10-15 hours of preparation and research before I even begin planting. Winter months are a great time to do this, because we often are not outside as much. Research species according to your soil type (acidity, organic matter, etc.) and carefully consider how much water will be retained in that area. Factor in sun exposure both in it’s current state, but also imagine the area once the plants have reached their mature sizes. How might this change your design?

Once I have the basic questions answered, I can then start looking at individual species and seeing what looks good together on paper. I will go through 3-5 different designs and purposely make myself change out some of the species in order to think outside of the box. Here are a few factors to consider:

- What is my top story tree? Will it produce nut or fruit? Will that impact my soil acidity over time? How tall will my center piece trees get? Will that impact my shade?

- Do my understory trees or shrubs have compatible soil requirements?

- How it my spacing? What will this look like in 3 years? In 10 years?

- Do I have at least 4 layers in my food forest?

- Have I including at least one nitrogen fixing plant in my system (legume, locust tree, clover, etc.)?

- Is there multi-seasonal interest for the eye? For nature?

- Have I considered season-long pollination?

- Do the plants that I have selected require a male and female plant for fruiting?

- Do my colors and leaf textures work well together?

Finalizing Your Midwest Food Forest Design

Once you have created a few different drawings of your layout, I would recommend sitting on it for a few days and then coming back to it later. Run the ideas by a friend and get their feedback. When I was initially planning my layout, I incorporated too many alkaline loving plants next to my blue berries, which do best with slightly acidic soils. I was so focused on the fruit and berries that I liked, and the way they would look together, that I missed a pretty big piece of the puzzle. The result would have been an environment where likely neither would have thrived, so I was relieved to have the insight from another permaculture eye.

Once you have created a few different drawings of your layout, I would recommend sitting on it for a few days and then coming back to it later. Run the ideas by a friend and get their feedback. When I was initially planning my layout, I incorporated too many alkaline loving plants next to my blue berries, which do best with slightly acidic soils. I was so focused on the fruit and berries that I liked, and the way they would look together, that I missed a pretty big piece of the puzzle. The result would have been an environment where likely neither would have thrived, so I was relieved to have the insight from another permaculture eye.

Before planting, plant on spending at least 10 hours of researching and planning out your design. As you plan, research various species, their growing zones, and read the reviews of others online. Often plants will say they will work in certain zones, but after a few years of consumer reviews, they change the rating on the species. For this reason, I tend to stay away from varieties that have not been tested in my region or ones that I am unable to find adequate reviews.

Personally, I like to order plants from places with one zone colder climate, so I know they can take the various types of weather we experience in the Midwest (KCMO).

The second part of this article will be available next week, including a few options in planting species for a wood-edge (sun/shade) area with clay soil structure. In the upcoming article you’ll learn how to amend the soil, perform bio-remediation for areas that may have had pollutants, and how to space the plants appropriately. The next article will include pictures of a newly planted food forest and close up pictures of the various species used in it’s design.