Seasons of change and transition are often challenging to navigate, no matter how many seasons of life one has experienced. As I am in the midst of one of those seasons myself, I am continually asking myself, “Why is this so challenging?” The answer to that is so simple, it is often overlooked. In short – People. People and relationships are complex, ever-changing, and the most precious commodity in the universe. Learning to navigate our journeys while being centrally focused on people are essential tools in a permaculturists belt. These lessons in lifestyle permaculture are a reflection of one of the core components of the practice – People Care. While many articles, blogs, and videos teach the earth care and money making principles of permaculture, the aspects of inter-personal relationships are often underplayed. When ignored though, the system goes out of balance. In most cases, earth care is the “what”, fair share is the “how”, and people care is the “why”. Without the foundational WHY being cultivated, the practices we build on top do not matter that much.

Have you ever been in a season of life when you lost your WHY?

In 2007, I was a part of a group of educators who helped found a small private school in South Kansas City. Over the last decade, The Daniel Academy went from 65 students to over 300. We purchased 18.5 acres of land in the city and an old church campus to hold our classes. Immediately, mentoring these young adults became my “why” and the fuel for my teaching job. Everything I did from that point forward was for kids and to see them thrive in the context of healthy families. Creating a school that was more of a community than an educational sphere became a foundational value that I functioned from. In 2010, we started a gardening and permaculture class for the junior high and high school students, and every quarter had between 5-35 students, depending on the season. Over the years, I can still tell you which students planted which nut tree groves, which families paid for and planted the apple trees, which students planted the wildflowers, and who helped plant the understory in the food forest. I can still picture some of my first students, Graham, Christopher, Becca, Bria, and Austin out in the courtyard planting Missouri native wildflowers.

This year, for multiple reasons, I came to the realization that my time at the school was nearing an end. I had been sensing the transition and have a burning desire to take the impossible step into “the next assignment” (forgive my teacher talk). I am not the first one to have been here, nor will I be the last. We have all been there, in that painful place between the last season of life and the ambiguous next season. We have all felt the intense series emotions that accompany transition and asked the question, “How in the world am I ever going to get there?” The answer, like most in life, can be found in the garden. Permaculture practice does not end at the garden gate, in fact, it often begins there.

It is important to embrace tough seasons, challenging relationships, and trying times. After all, the very best gardens have a foundation of crap.

Lessons in Lifestyle Permaculture

Here are a few of the lessons in lifestyle permaculture that I have been learning. Perhaps it will help others in learning to navigate their seasons from one garden to the next.

1 – Understand your WHY

For me personally, I have always thought I was project driven. I thrive when there is a large task, project, or an event to plan. My heart comes alive in doing acts of service for others and being able to see them loved well. In December 2016, when I moved my desk, some of the chickens, and my other belongings out of the private school and into my home, I began to reimagine my ideal backyard set up. It was my opportunity to give order to my own castle. So, I arranged my desk to look at the back window, and had the chickens in the perfect line of sight. I rearranged my shed and garage, and started drawing up the next phase in my urban permaculture yard. It was / is a picturesque set-up that I can find few practical faults with. The last two weeks, looking out from my desk, I had a profound realization…

I do not like chickens that much. Even heavier… I do not really enjoy permaculture (itself) as much as I thought. Believe me, I was shocked. For three days, I sat and pondered while I continued to clean and organize, until the realization hit me. There are no sounds – no people. At the school, I was surrounded by kids, teachers, families, and parents. Every twenty minutes someone would come into my office to sit, talk, or just hang out. At the time, those interruptions were annoying and seemingly inconvenient. Now, being at home, I have realized that those students, kids, and families were the WHY behind the projects.

It’s true, I raised chickens primarily because it gave me a platform to interact with students. I taught 11-12th grade English because I loved seeing the “ah-ha” moments on their faces. I worked in my office with the door open so that parents and kids could come inside and visit. In fact, I even studied permaculture to give me a connect point with families outside of the traditional classroom. This entire time, I thought the projects, hugel-swales, raised beds, writing assignments, and books were my passion, but I was wrong. I misunderstood my own passion, which was really caring for PEOPLE.

2 – Strengthen remaining connections and build new ones

When undergoing seasons of transition, take Bill Mollison’s advise, “For every element, establish 3-4 connections.” Often when our life experiences change, we focus on what was lost. We look too heavily on the “sink” or the waste. This is easy to do, because we experience a sense of grief and mourning, which is healthy and normal – for a moment. Instead of staying in the place of loss though, we must look to what remains. Strengthen the connections that have weathered the storm, because often times those are the most healthiest points anyway. In an ice storm, the branches that break off are often the ones that likely needed pruning anyway. Focus on restructuring from the remaining framework and make additional connections to strengthen that which remains.

Often times, remaining connections will experience stress and pain, but instead of ignoring it, tend to it. Let the wound have “sensation”, because it’s a sign of life still existing there. Apply healing salve to broken limbs, set bones right again, and prune back the dead leaves. Focus on the trunk and root system and be prepared to nurture it over a period of time. Yes, recovery takes nurture, and most importantly, nurture from community.

Use these times of transition to build new connections. Add limited additional elements to your system. Not only will this help you learn something new in the process, but it will also take your mind off your circumstances. Instead of focusing on the valleys, look up to the hills and find the longest-highest contour point (where the water comes from). So, let’s be practical. In times of life transition, embrace relationships where you can be vulnerable. Let people call you higher. Invite people into your home, even if they don’t invite you first. Make the phone calls you have been dragging your feet on, and try a new project or two in order to keep the hands busy. Don’t shrink back – take a step forward.

3 – Think long-term and begin with the end in mind

Seasons of loss are followed by rebirth. Death is not the end, but rather a beginning. In the garden, when sometimes dies, we do not throw it away and remove it from our property. We compost it and re-add it back into our system in a changed (often healthier) form. Even diseased plants can be composted, but need to be treated with a higher core temperature to kill the bacteria, but after a short time (18-days in the Berkley method) the compost can be generally re-added to the garden without fear.

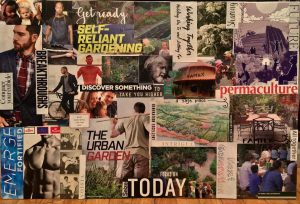

One of the practical strategies in lifestyle permaculture is to begin with the end in mind. If you want a long-term food forest to feed your children, don’t limit yourself today by only planting lettuce and tomatoes. In our every day life, one of the practical tools I use is creating a vision board. As yesterday was National Vision Board Day, I had 15-20 folks over last night to just dream about their futures and get a little creative. Participants cut images and words out of newspaper and magazines, and glued them on their own vision boards to hang up in their offices, closets, and bedrooms. Keeping the longterm vision in front of us on a daily basis helps keep our eyes fixed on the bigger picture and allows us to visualize what the future might look like. For me, seeing my vision board every day helps me make smaller decisions that are like “steps” toward the bigger goal.

4 – The problem is often the seed of the solution

Problems are real and cause stress. Conflicts are painful. Relationship bumps are challenging and stir the heart. Emotions, both positive and negative, are real and should be experienced without shame. Getting stuck in the place of pain is obviously never the goal, but glossing over it is not helpful either. Often times, the pain points we experience in transitional times are the seeds that we need for the days ahead. I remember Geoff Lawton saying, “You don’t have a slug problem, you have a duck deficiency.” The slugs are natural parts of the ecosystem and should not be reason to burn an entire crop at the first sign of their presence. Their presence is an indicator that the system is in need of attention and nurture to bring it back into balance. The problem is often the solution. Those slugs, with the introduction of ducks, can be turned into eggs, meat, and fertilizer. Not to mention, those problematic slugs provide hours of entertainment for families when we get to watch the ducks on a feeding frenzy. The problems do not indicate the end or death; instead they merely indicate a system which needs nurture (not neglect).

When using permaculture as a lifestyle model, ask yourself some key questions about the problems you are facing:

A – What is the pain point I am experiencing? Why does it matter to me?

B – What is the opposite of this pain point? How can I build toward this to create a better reality?

C – What type of nurture is needed in order to bring about this change? What connections need strengthening? What pests / diseases need to be “heated up” in order to bring back the balance.

5 – Polyculture not Monoculture

In the garden, planting a mono-crop is often easier in the short-term. It requires no other connections with plants, little thinking, and can be accomplished in a short amount of time. In the long-term though, the mono-crops experience nutrient deficiencies, devastating disease, require fertilization, etc. When the mono-crop is finished producing it’s fruit, it is done. Nothing next. In contract, a polyculture with multiple, perennial species, a different approach is taken. It takes more careful planning, time to evolve, and a little nurture, but it will create a balanced and self-sustaining system that has perennial abundance. Polyculture systems experience less disease, continue fruit and supply, and a supply for both humans, insects, and animals. Polyculture systems create the platform for abundance.

When crisis arises in our personal lives, we often bunker down and try to hide ourselves away. After a rough day in the office, I would frequently go home and have a glass of wine and a PINT of Ben and Jerry’s Ice-cream. Nursing my wounds with ice-cream is an unfortunate go-to, but is usually followed the next day with regret. Likewise, instead of isolating ourselves in our momentary hang-ups, allowing ourselves to be vulnerable in the place of community is a much healthier approach. When your brother falls down, stretch out a hand to help him up. When a neighbor is cold, give them a blanket and food. Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. Sounds simple, but it is much easier said than done. It requires us to establish and nurture connections, and be vulnerable. That risk is always worth it.

It is all about the WHY

At the end of the day, what I have discovered in this season of transition is that understanding our foundational WHY is the key to thriving in times of change. For me, these lessons in lifestyle permaculture have taught me to value family before function. People are the foundation stones for any project, and at the very center of my being is an innate desire to be in family and a part of a community who is in it for the long-haul. For me, that is permanent culture. People care is the foundation of my journey in permaculture.

Why do I do permaculture? I believe that families today deserve the very best food, produced in the very best way, and that kids deserve to live in a community that is flourishing with abundance. I do permaculture because when I leave the earth, I want to leave it to the next generation BETTER than I found it, which means that merely “organic” is not enough anymore. We need regenerative systems to heal the damage we have already caused. Millennials, we are way past the point of needing “sustainability” and organic food – we need a culture that heals families, land, and hearts. We have to leave this planet better than we found it or we have failed. Because of our endless greed, narcissism, and egocentrism – we will have failed the ones who will come after us. This is why permaculture is more than tomatoes – it’s about a legacy.